All the way back at E3 2006 (oh E3, how I miss thee), Square Enix would announce the next chapter in its tentpole JRPG mega-franchise. Spearheaded by not one, but two Final Fantasy titles destined for Sony’s PlayStation 3 console, attendees and watchers of the show would be introduced to Final Fantasy XIII, which would go on to release in 2009, and Final Fantasy Versus XIII, which would go on to not be released – at least in its initial form anyway. At this point in time, Final Fantasy Versus XIII was set to be directed by Tetsuya Nomura, the very same chap who had directed the 2005 CG movie, Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children, before going on to direct Final Fantasy VII: Remake, which would release in 2020. So at the very least, there was a comforting pedigree steering that particular ship.

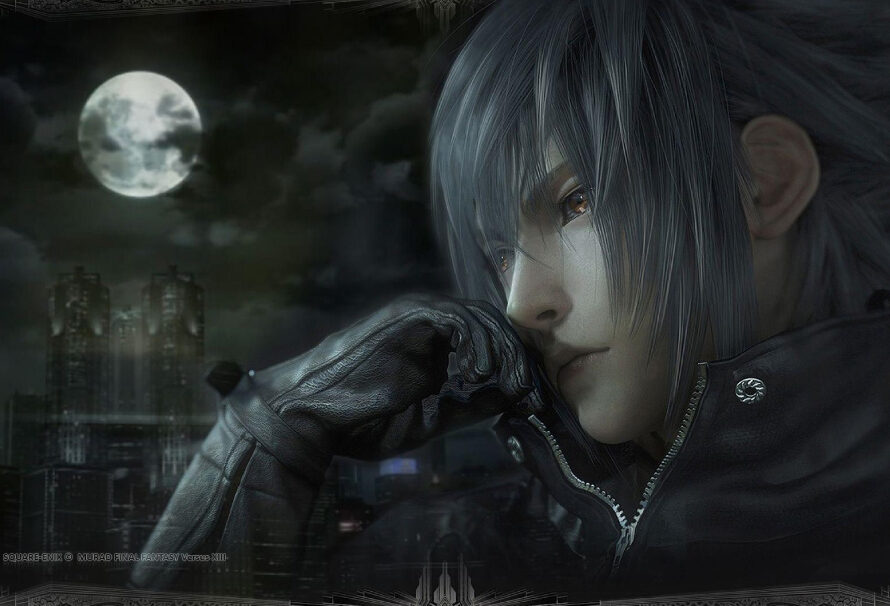

The initial reveal of Final Fantasy Versus XIII showcased a title that was very much at odds with the somewhat lighter, more shiny sci-fi themes that were glimpsed in the reveal for its series stablemate, Final Fantasy XIII. Leading with weighty quotes from Shakespeare about the nature of man, good and evil, Final Fantasy Versus XIII not only set its stall out as an epic, gothic RPG, but it also introduced us to the character that would go on to be the main protagonist of Final Fantasy XV ten years later – Prince Noctis. Though we’re getting a little ahead of ourselves here.

After an extended period of silence, it soon came to light that the direction that Final Fantasy Versus XIII was taking was at odds with ideas held by members of the development team, causing the game to be postponed. Compounding this delay was the fact that Square Enix was also grappling internally with technological barriers posed by both the ageing PlayStation 3 hardware and its Crystal Tools engine that was powering Final Fantasy XIII. Essentially, the engine was causing so many internal issues that members of the development team working on Final Fantasy Versus XIII were constantly being pulled into supporting the development of Final Fantasy XIII, just to make sure that the highly anticipated title shipped in a reasonable timeframe.

Making things even worse still was that when Final Fantasy XIII Versus did finally start development in 2010, it was almost immediately shoved straight into development hell again because Square Enix’s second bite at the MMO apple, Final Fantasy XIV, was struggling badly on release. In fact, that might be selling the situation short because Final Fantasy XIV had suffered such a botched launch and was riddled with so many bugs and technical problems that the team decided to rebuild the whole thing from scratch. Can you guess which Final Fantasy title had its developer resources seconded to aid in this venture? Yep, that’s right – once again the team working on the long-gestating Final Fantasy Versus XIII was once again pulled off the project to fight fires located elsewhere.

By the time 2011 rolled around the world was somewhat shocked to discover that Square Enix had decided to release a new trailer for Final Fantasy Versus XIII. Intriguingly, this latest batch of footage would show that Final Fantasy Versus XIII had taken something of a right turn, easing up on the relentless grimdark of its original reveal in favour of a lighter, more grounded setting, together with glimpses of green-stuffed rural areas that were utterly missing from its initial unveiling. Beyond an obvious tonal shift, this latest trailer for Final Fantasy Versus XIII not only gave eager fans a look at the two new characters that would eventually resurface in Final Fantasy XV, Noctis’ pals Ignis and Gladiolus, but also a peak at the real-time combat would also feature, including Noctis’ natty ability to teleport across the battlefield.

Though it wasn’t called Final Fantasy XV by name at that point, what we saw in 2011 was essentially the first bonafide footage from the game that would take that name and release a good five years later. Under the stewardship of new director Hajime Tabata, Final Fantasy Versus XIII completed its transformation into Final Fantasy XV and in doing so found itself formally integrated into the Fabula Nova Crystallis universe, sharing common themes and lore with other titles that exist within that setting.

More than that, Final Fantasy XV presented the series at large with something it had never seen before – a truly seamless open world which begged to be explored and in which secrets and side quests could be found in abundance. Further afield, Final Fantasy XV would innovate yet further still, giving players the first proper JRPG road trip odyssey that no games before or after have dared to mimic. This resulted in a genre-defining offering that made it easy to buy into its quartet of impossibly well-styled protagonists, because Final Fantasy XV invited you to be with them during all of their ups, and downs, countless banter and even when they’re just off goofing about cooking meals, fishing and more besides. Put simply, if you were a long-time Final Fantasy fan who was becoming burned out on the series, or a franchise newcomer looking for an epic JRPG that did things a bit differently, Final Fantasy XV was and remains a superlative entry in Square Enix’s long-running marquee intellectual property.

Ultimately what we got with Final Fantasy XV was a title that somewhat violently pushed back against the angsty, dark origins that Final Fantasy Versus XIII promised a decade earlier. With Final Fantasy XV, we had a title that very much extolled the values of brotherhood, friendship and togetherness in direct opposition to what looked to be the brooding and almost stiflingly grim tone that Square Enix’s latest offering was shooting for in a previous life.

Taking all of that into account, while Final Fantasy Versus XIII’s metamorphosis was long-gestating and certainly very drawn out, the result was arguably worth it and helped to give Square Enix’s most recognisable franchise a sorely needed shot in the arm. All the same, it’s difficult to not keenly feel a pang of curiosity about what could have been had Final Fantasy Versus XIII stuck to its original vision and not found itself as comprehensively railroaded as it did, time and time again.